INTER_SITE VAI Newsletter article written by collective members Pádraic Barrett and Kate McElroy ahead of Pallas Projects Artist Initiated Projects Exhibition, Error: /Undefined, Dublin 2023

data_bodies, A text by Laurence Counihan in response to The Engineering of Consent II, The Marina Warehouse, 2021

Dust To Dust, A review by Paul Connell in response to The Lavit Gallery exhibition Confluence featuring Pádraic Barrett and Orla O’Byrne, 2020

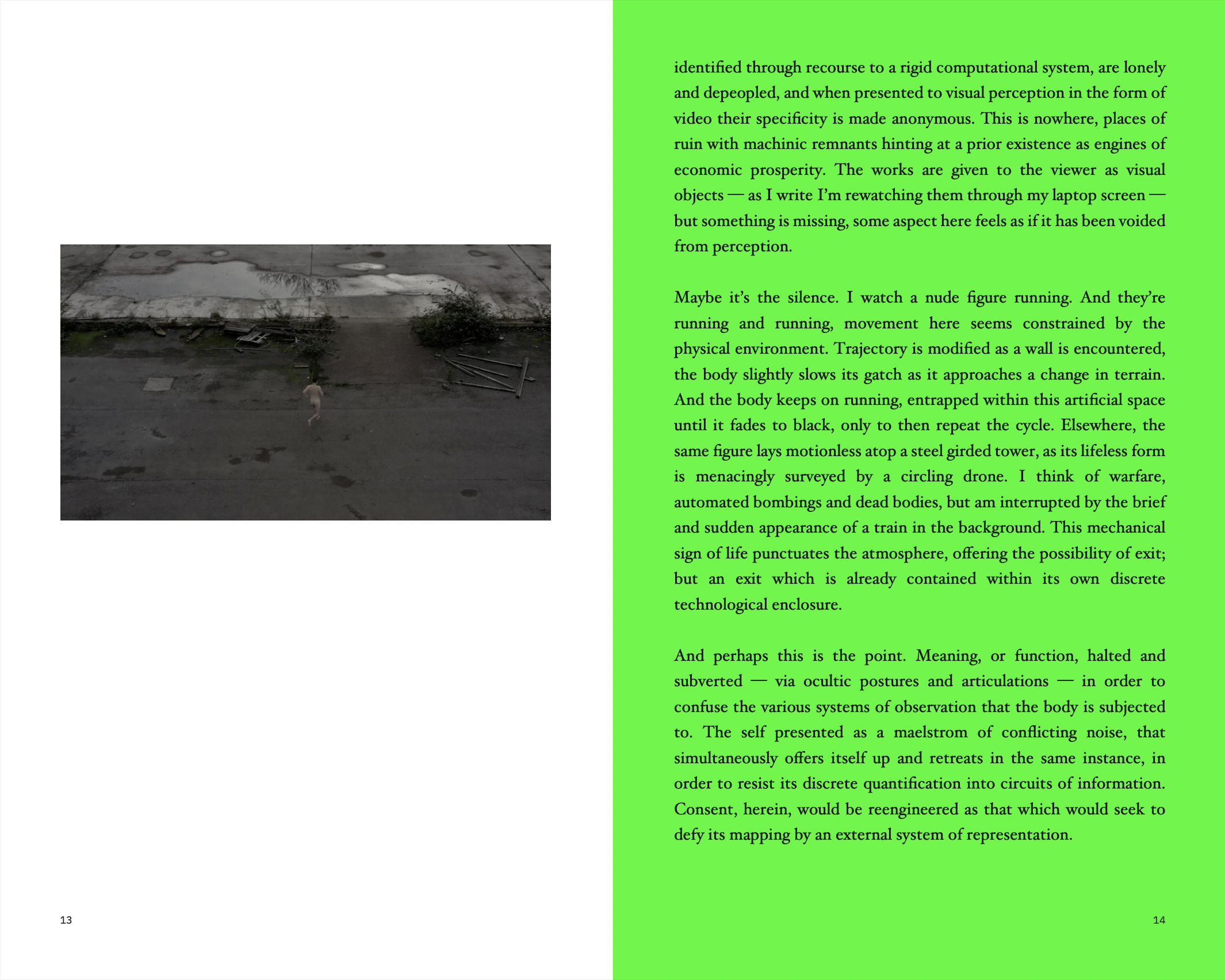

“All I know is a door into the dark”, opens Seamus Heaney’s timeless lament of the male condition. It is a venerable door, this gateway, one that is knocked on but seldom answered. Barrett’s work demolishes whatever door stood meekly between him and the dark and he welcomes it, he taunts it; marrying himself to the veil between, but never committing to either side. There is no more binary for him here; there is no more life or death, but something that oscillates between the two, exponentially, tangentially. The artist’s performances are both baptism and burial. Large format videos of the artist absorbed in shamanistic rituals occupy the floorspace, where we appear to witness from a great height above, or as if stumbling upon a corpse. Barrett imposes on us from what side of the veil we are observing, toying with fetish and the voyeur. We watch the artist subject himself to the elements, vanish beyond them and then return a harbinger, a messenger. Questions of masculine legacies and inheritances leak from the imagery of the land and the labourer, where the artist motionless, worships and blasphemes, as Heaney put it: “Set there, immoveable: an altar where he expends himself in shape and music”. Rhythm and breath and black and white and earth and water. Laden with a seductive masochism, these become instruments of insight and vicious mockery. The artist’s live endurance based performance in the gallery flirts with the abject. We are invited to an intimate burial where the artist in silk pyjamas and a lace veil is ceremonially freckled, coated and baptised in soil. There is no vault or grave, but a humble white panel. His mausoleum, or birth canal is something beyond the visible. The shovel is laid down, and earth trembles on heaving slumber.” A last one so unanswerably landed the staked earth quailed and shivered in the handle?” Revisiting the site some days later, and finding his resurrection indicated by the impression of the artist's body in the sculpted earth, candidly relates to the confluence between it and the onlooking partial casts.

A text by Alannah Matthews in response to Pádraic Barrett and Orla O’Byrne’s exhibition Confluence, The Lavit Gallery, 2020

‘Confluence’ The junction of two rivers. The act or process of merging. When two rivers meet, they bring with them a thousand lifetimes of echoes, whispers and battlecries. Two life forces bleed into one, and while I’m no marine biologist, I know that something very powerful lies in that moment (or series of moments) during which two rivers merge. Today, within these very four walls, we occupy a moment of confluence, and experience two rivers become one. We are surrounded by works which whisper of times gone by, and speak of the times we live in today. On the opening night of this show one week ago, I came armed with pen and paper. I wanted to note every phrase or word which leaped to mind as the work revealed itself to the public. Delicate Sinking Wavering Planted Remains Flickering While experiencing Orla and Padraic’s work, I felt a feeling that I’ve struggled to articulate exactly since. The gallery was full of bustling groups and wine glasses, but inside, I felt a stillness. The sort of stillness you feel when looking at photographs from the 1920’s or castle remains in the countryside. A stillness which - when you think about it - isn’t very still at all. It carries echoes of movement and history, captured in a single moment, eternalised before your very eyes. Themes of reflection, preservation and renewal, leap from the artworks in this show. Padraic Barrett’s work responds to archetypal patriarchal traditions in Ireland today - such traditions which form a weighted, complex pressure on what it means to be ‘man’ in this country. Recurring ideas surrounding rebirth, death, ritual and burial present themselves throughout the work. Orla O Byrne’s exploration lies in ideas of absence, discovery and preservation of the human experience. The work offers frozen moments of preserved movement, and ever-moving depictions of the human form and nature, probing us to pause and be mindful as the works reveal themselves to us in their final form. On the opening of ‘Confluence’ Padraic performed a live piece titled ‘Bury the Past - Heal the Land’. Lying on white board - reminiscent of an altar piece - his body is flat, limp, silent. The mood in the gallery is tense and still, I bite my nails as a shovel scrapes the wooden floor, showering the artist’s frozen body in mud. With each scratching movement of shovel, ideas surrounding ritual, grief and nameless graves spring to mind. I think about bog bodies and shallow graves and the wheaten hue of skeleton fingers as crumbling soil reshapes our view of his hands and feet. I think of men killed for not being the men Ireland wanted, and wonder if that’s what Padraic is thinking too, as he lies in a state of quiet ritual. Days later I return and there is no body, only dark imprints on a low mound of mud. The shovel lies defiantly in line with the site of the performance, surrounded by frustrating remnants of mud, bits left behind. To my left are Orla’s sculptures. The Eleanor casts lie and stand on blackboard, serenely staring at the remains nearby. I wonder - for a split second - what they are thinking, how they might feel. Cast from a monument made from Coade stone - invented by Eleanor Coade, an artificial stone businesswoman - they sing from an 18th century existence of defiant femininity, in a Europe cast for men. Their presence is strong, proud, but certainly eerie. Frozen faces from the past. I move around the space to watch Padraic’s video installations. I look down at ‘Transcend’ and feel myself reeling as the artists spins and spins, almost like a dancer, almost in quiet turmoil. The figure is faceless. With ‘Caul’ I feel as though I am drifting between the art and reality. Waves lap over a still body, face down and with a face hidden by the afterbirth of a cow. I’m more hopeful now, as if a new life has been born. ‘Fall of Man’ stands tall and proud. There is an air of majestic resilience in the work. The figure stands. A face remains hidden, reminding me of the universal nature of this work. I think of baptism and ritual, events often marred in my mind by their Catholic connotations. I feel as though something is being reclaimed. I walk to ‘Restless’, Orla’s projected drawing piece. Emerged in a series of gradual movements, I am quickly lulled into a state of contemplation. I am reminded again of the endless possibilities drawing holds. This is drawing with a weighted narrative of human movement. With the emergence of each chalk mark, I play a guessing game of how the model might have moved, how she might have communicated with the artist. I forget that this piece entails projection, and instead, I remember the power of preserving the human condition. In ‘A Drift’ I am moving with nature itself as ripples of water emerge to say hello. Both works hold a cast-like presence as they reach their final form, as if bowing in solidarity to their plaster Paris sisters nearby. I leave the gallery more comforted than I had entered. I had entered a space to find two rivers merge. Both spoke of defiant repetition and unearthing of human experience to remind us of both the strength and fragility the human experience entails. There were moments of grief and moments of revival, but most importantly, there was hope. On a day like today - one of political uncertainty in - it is more strengthening than ever to hear the voices of two artists who are not afraid to unearth stories of the past, and question how contemporary narratives are formed. Thank you Orla and Padraic for making defiant, sensitive work which reaches everyone.